Google has been long synonymous with the unofficial motto “Don’t Be Evil,” a clause that encapsulated everything about its core values, one that it expects every employee and Board member to “follow both in spirit and letter”. However around the time the search titan was reorganised under a new umbrella company Alphabet in 2015, the motto received a fresh coat of paint:

“Don’t be evil.” Googlers generally apply those words to how we serve our users. But “Don’t be evil” is much more than that. Yes, it’s about providing our users unbiased access to information, focusing on their needs and giving them the best products and services that we can. But it’s also about doing the right thing more generally — following the law, acting honorably, and treating co-workers with courtesy and respect.

The Google Code of Conduct is one of the ways we put “Don’t be evil” into practice. It’s built around the recognition that everything we do in connection with our work at Google will be, and should be, measured against the highest possible standards of ethical business conduct. We set the bar that high for practical as well as aspirational reasons: Our commitment to the highest standards helps us hire great people, build great products, and attract loyal users. Trust and mutual respect among employees and users are the foundation of our success, and they are something we need to earn every day.

More than just not being evil, it was also about “doing the right thing.” Or so it was until early this May. Not anymore. Because, this is how it looks now:

The Google Code of Conduct is one of the ways we put Google’s values into practice. It’s built around the recognition that everything we do in connection with our work at Google will be, and should be, measured against the highest possible standards of ethical business conduct. We set the bar that high for practical as well as aspirational reasons: Our commitment to the highest standards helps us hire great people, build great products, and attract loyal users. Respect for our users, for the opportunity, and for each other are foundational to our success, and are something we need to support every day.

Whether the change was intentional, we may never know (the final line still reads: “And remember… don’t be evil, and if you see something that you think isn’t right — speak up!”), but it does speak volumes about the changing priorities for the company, even going to the extent of eschewing everything it stood for as it faces continuing pressure to expand.

The shift in stance became more apparent after The Intercept revealed the search behemoth’s plans to re-enter the Chinese market, more than eight years after it pulled out of the country over the government’s efforts to curb free speech, block websites (dubbed the Great Firewall) and hack activists’ Gmail accounts. The move, ever since it came to light, has not only raised serious concerns about censorship and surveillance, but also marks a giant volte face for the company after it famously decided it was no longer comfortable with censoring search results back in January 2010.

Since then though a lot has changed, with the leadership mantle passing from Sergey Brin to Sundar Pichai (who has shown a keen desire to come back) and China emerging a huge smartphone market that remains untapped for a lot of companies like Google, Facebook (China has surprisingly emerged the second largest ad spender on the social network) and Twitter, with the notable exception of Apple. Which also explains Google’s recent attempts at reconciliation: a new AI-focussed research centre that was opened late last year, the release of Files Go and a doodle mini-app for WeChat, the strategic partnership with Chinese retailer JD.com, and the re-introduction of Google Translate in the country.

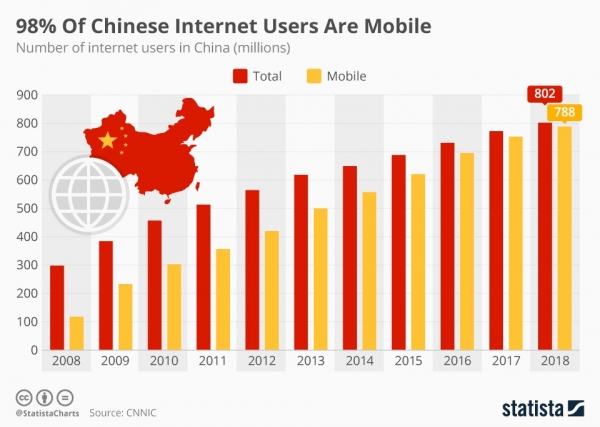

Ultimately for Google, sticking to principles and values won’t translate to earnings growth, and growth is still a top priority for most big Silicon Valley tech companies. And by choosing not to operate in China as a matter of principle, the company has only succeeded at ceding ground to local rivals like Baidu. That, and losing a valuable territory comprising of 800 million active internet users, of which 788 million (i.e. 98 percent) access the internet via mobile. The U.S., in contrast, has an estimated 300 million internet users.

Google may reiterate that its “commitment to the highest standards helps us hire great people, build great products, and attract loyal users,” but in 2018, when it comes to re-entering China, it’s a market it can no longer afford to ignore, a moral compromise and a matter of choosing between the lesser of two evils. And as Alex Shephard notes, “It is simply a big company that will do whatever it takes to get a little bigger.”

Here is a quick timeline of events:

Aug. 1: The Intercept reports that Google is working a new project, supposedly codenamed Dragonfly, that has been in development since last spring, citing internal documents leaked by a whistleblower. The secret project is said to involve an Android app that “will blacklist websites and search terms about human rights, democracy, religion, and peaceful protest.”

Aug. 2: The Information (paywall) reports that Google is also developing a news app exclusive to China that will comply with local censorship laws.

Aug. 3: Google is also looking at partnering with local cloud service providers (including Tencent Holdings) to bring Google Drive and Google Docs to China, Bloomberg reports, in a move that sounds a lot similar to Apple, which recently migrated all of its Chinese users’ iCloud data to a local operator named GCBD in order to comply with local regulations.

Aug. 16: In the wake of internal backlash against Google’s supposed entry into China, CEO Sundar Pichai informs employees that the moves being undertaken are just “exploratory” and that the company isn’t close to launching a search product in the country.

Sept. 14: Google is also reportedly building a prototype system that would tie Chinese users’ Google searches to their personal phone numbers so as to meet local censorship requirements, reports The Intercept, drawing further opposition inside and outside the company over its controversial decision to re-enter the country.

Sept. 26: At a Senate hearing on data privacy, Google’s chief privacy officer Keith Enright confirms the existence of Project Dragonfly, but dodges questions on what exactly the project entails, stating “I am not clear on the contours of what is in scope or out of scope for that project.” Ben Gomes, Google’s head of search, tells the BBC that “Right now all we’ve done is some exploration, but since we don’t have any plans to launch something there’s nothing much I can say about it.”

Oct. 4: The U.S. government urges Google to halt work on Project Dragonfly, and in general any business practice that would abet Beijing’s oppression, reports The Wall Street Journal.

Oct. 11: Google’s China-specific search engine may be launched in the next six to nine months, contradicting earlier reports that the company’s plans were still in the exploratory phase, according to a leaked transcript of an internal meeting that occurred on July 18, via The Intercept. An anonymous Google source calls Ben Gomes’ earlier comments (refer to update on Sept. 26) “bullshit,” while Gomes has the following response when reached via cellphone: “I can’t hear anything that you are saying, I can just hear that you are talking,” before hanging up.

Oct. 15: Google CEO Sundar Pichai officially confirms company’s plans for a China-focussed search engine, adding internal tests have been very promising and that the country is important given “how important the market is and how many users there are”. “It turns out we’ll be able to serve well over 99 percent of the queries,” he said, stating that, “People don’t understand fully, but you’re always balancing a set of values (providing access to information, freedom of expression, and user privacy) … but we also follow the rule of law in every country.” Google’s Project Dragonfly and Project Maven (a Department of Defense project to build AI and facial recognition technology for drone warfare) have been both controversial, with employees and the larger tech community seeing the company’s actions as crossing an ethical line.

Nov. 21: Alphabet chairman John Hennessy underscores the struggle with launching a search engine in China. “The question that I think comes to my mind then, that I struggle with, is are we better off giving Chinese citizens a decent search engine, a capable search engine even if it is restricted and censored in some cases, than a search engine that’s not very good? And does that improve the quality of their lives?,” Hennessy tells in an interview with Bloomberg, adding, “Anybody who does business in China compromises some of their core values.”

Nov. 27: A growing group of Google employees sign a letter urging the search giant to end the “Dragonfly” project aimed at creating a censored version of its search engine in China. “Many of us accepted employment at Google with the company’s values in mind, including its previous position on Chinese censorship and surveillance, and an understanding that Google was a company willing to place its values above its profits. After a year of disappointments including Project Maven, Dragonfly, and Google’s support for abusers, we no longer believe this is the case. This is why we’re taking a stand,” reads the letter.

Nov. 29: Key executives involved in Project Dragonfly, including Google’s China head Scott Beaumont, were dismissive of surveillance and security concerns arising out of launching a search engine that could associate users’ phone numbers (and their location) with searches seeking “information banned by the government,” reports The Intercept, adding, they “shut out members of the company’s security and privacy team from key meetings about the search engine, the four people said, and tried to sideline a privacy review of the plan that sought to address potential human rights abuses.”

Originally published at therarefied.blogspot.com.The story has been updated on Nov. 30 to reflect the latest developments.

Connect with us