Dominic SimonelliBlockedUnblockFollowFollowingDec 2

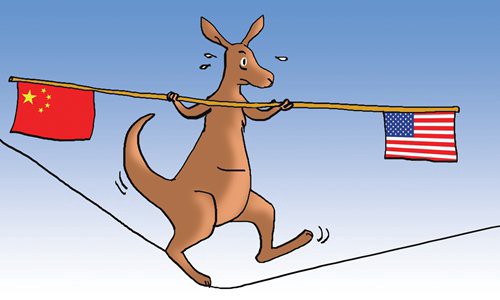

Trump’s ‘America first’ doctrine is leaving one of the United States’ closest ally in the Asia-Pacific with tough decisions to make — A perspective from Australia.

On May 14th 2018, after much international chagrin the United States opened its new Embassy in Jerusalem. President Trump’s controversial move marked a departure from decades of US foreign policy whereby Tel Aviv has been the base of the country’s diplomatic mission in Israel.

A hemisphere away, Australian leaders seriously pondered following suit. The new Prime Minister Scott Morrison strongly supported President Trump’s decision, and argued if Australia were to move its own embassy to Jerusalem it would be a commitment to the long-fabled Israel-Palestine two-state solution.

But this unexpected move rattled Australia’s regional partner Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim majority country, which sits a mere 200km (124 miles) from Australia’s northern shores and is a strong supporter of Palestine. In response, Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo threatened to halt the implementation of a free trade agreement between the two countries that has been in the works since 2010 and worth over $US15 Billion.

A century-long alliance

Australia following US President Trump into unorthodox territory was a controversial move; but wherever the US goes Australia is often no more than a few steps behind.

The two continent-sized countries have always been close and their relationship goes beyond their shared language and cultural legacy from Great Britain.

During Britain’s decline in the early-20th century, the fledgling Australian nation looked for a new shining city on the hill, which it found in the United States. From WWII onwards, Australia has needed the US’s military might which has maintained a strong hold in an otherwise unstable region.

From the US’s perspective, Australia has always been a bastion of Western democracy in the otherwise foreign and turbulent Asia-Pacific. The ally is crucial to maintaining order in the Asia-Pacific and containing China’s soft power relations with many poorer island nations.

Since signing the 1951 ANZUS military treaty, Australia has been the US’s only ally to fight along side it in every major conflict for 100 years. Today, the US maintains a significant military presence in Northern Australia and this was recently boosted by the deployment troops, aircraft, and artillery battery.

The two states, along with Britain, Canada and New Zealand, form part of the crucial Five Eyes intelligence alliance. The spy network has been expanding their intelligence-sharing specifically to combat increasing Chinese interfering in foreign operations and investments.

Economics further links the two as US is Australia’s largest foreign investor, with two-way investments flowing back and forth each year now totalling more than $US1.1 trillion.

The ‘panda’ in the room

But while Australia has one finger in America’s apple pie, it has another in China’s. China’s rocketing growth has strongly benefitted Australia, especially through raw mineral and ore exports. This helped sustain Australia through the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and, as Professor Tony Walker writes, ‘no other country, relatively speaking, has benefited to quite the same extent from China’s extraordinary development’.

The land down under’s economic success is intrinsically linked to Chinese economic policy. 2016–17 saw Australia export over $US70 billion to China, accounting for nearly 30% of total Australian exports. When China sneezes, Australia catches a cold.

China’s growing middle class means Chinese nationals are coming to Australia in higher numbers every year. Over half of all tourist spending is from Chinese holidaymakers heading to Australia. As of 2018, over 100 thousand Chinese students currently study in Australian universities not to mention the sizeable minority Chinese community in major Australian cities.

But recently the relationship has soured somewhat, particularly over disputes over Chinese involvement in Australian domestic affairs. The Australian government mirrored the US’s decision in banning Chinese state-owned firm Huawei from involvement in its national telecommunications infrastructure.

China has taken notice and become suspicious of the US-Australia relationship. Beijing declared says Australia needs to do more to develop mutual trust if wants to continue doing big business.

Between a rock and hard place

Things are not all rosy between the US and China either. At the recent Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, the US and Chinese delegations clashed over World Trade Organisation reforms to reclassify China from its ‘developing country’ status and ongoing trade war over perceived Chinese ‘unfair’ trade dealings.

APEC negotiations were inconclusive and Australia was left smiling awkwardly as the two giants refused to even sign a joint statement for the first time in the Summit’s 25-year history.

Australia has serious cause for concern. When Trump slapped a 10 per cent impost on roughly $US200 billion of Chinese imports Australian shares tanked. After speaking recently with Chinese leader Xi Jinping at the G20, Trump suspended his threats to add tariffs on additional $US267 billion which would have struck a further blow to Australian markets.

Decisions to be made

Sticking close to the US’s side has historically been advantageous for Australia. But as Professor Rory Medcalf argues, Trump’s radical re-positioning of American foreign policy means Australia is now finding itself in a precarious place. Indeed, Oz has been left in limbo as a country not willing to go down the traditional path hand-in-hand with the US President’s worldview, yet not in a position to go off on its own.

Australia’s trade movements into Asia rely on Trump’s continual support for the US maritime presence, there to counter the increasingly hostile China protecting its shipping routes in the South China Sea. Yet siding too closely with Trump risks creating a bigger fissure in the already cracking China-Australia relationship.

As Tom Switzer writes, Australia has long been riding on two horses; with the Chinese now horse running one way and the American horse running the other, the Australian economic wagon is poised to be ripped apart. Australian policy needs to reconcile its China trade relations with its US security alliance.

If Australia follows Trump’s erratic anti-globalist policies, the country will undoubtedly be pushed into further disputes with neighbours like China and Indonesia and this could leave the country isolated.

One option could be rub shoulders with other regional middle powers such as Japan and South Korea which Australia’s second and fourth largest traders respectfully. All of these Asia-Pacific states have been hurt by Trump’s tariffs and fears he will withdraw hands-on regional support that acts to match China’s. How dynamics in the Asia-Pacific could play out without US involvement remains to be seen.

Australia policy makers must ask if it’s worth following Trumpian doctrine, whatever that may be, at the risk of angering key regional allies and endangering trade. Either way, there is some soul searching to be done.

Connect with us