Barrett RotheBlockedUnblockFollowFollowingDec 3

If you’ve heard of Flint, Michigan you’ll know that water infrastructure in the United States has opportunities to improve. Flint is, sadly, not an isolated incident and only 17% of utilities providers in the U.S. think they can cover operating costs, let alone refurbish their infrastructure, with current utility rates.

Much of our water infrastructure was designed almost a century ago and is growing more prone to failure. Natural disasters, chemical spills, terrorist attacks, negligence, severe drought, and run-of-the-mill human error all could bring about a sudden water shortage for the United States by overwhelming our infrastructure’s ability to respond in a crisis.

Our current water infrastructure is a recipe for disaster that will inevitably catch up with us, but if it fails in just a few places at the same time we’re in monumental trouble. A cascading failure in the most vulnerable parts of the United States might mean we need immediate assistance from foreign countries, and our current foreign policy seems unaware of that possibility.

A basic need with advanced problems.

We take potable water for granted in the United States. Showers, cooking, lawn irrigation, hot yoga humidifiers, and car washes all use high-quality water. The oil and gas industry assumes an endless supply of water for mineral extraction, while golf courses in Las Vegas have green fairways in July.

That comfortable status quo is coming to a rapid end, even though it’s not in the mainstream conversation of American politics. In fact, a November 2018 Gallup poll of political issues important to Americans does not include the word “water” in the results, and “environment” only garners interest from a meager 2% of respondents. Water scarcity is a future issue we’re largely ignoring, and a shortage might not be a problem that unfolds like slowly running out of gas, but instead (due to our failure to plan) could look more like us driving off a dry cliff.

Some of the world’s top minds are on the case though. Michael Burry, who foresaw the 2008 collapse of the U.S. housing market and made a fortune on it, has turned his attention to investing in water resources as the next domino to fall. Picture a Great Recession-sized event, but instead of condo prices falling we go to turn on our faucet and nothing comes out. That’s what Burry is seeing in his crystal ball.

Even a small disruption in a large U.S. city would mean hundreds of thousands of first-world city dwellers facing the worst days of their lives. New Mexico is ahead of the curve, having created a strategic water reserve in 2005, but most of the United States is tragically unprepared for a water emergency.

When a country has a sudden, unprecedented need for help, it can usually turn to neighbors and global allies for support. No nation is immune to needing assistance, even the United States sought help from the Mexican Army after Hurricane Katrina. But that was a different era in foreign affairs.

As U.S. foreign policy careens toward “America First” isolationism, it’s growing increasingly difficult to see a future of abundant goodwill toward a United States in crisis. When you’re desperately in need of help, a history of spurning the global community does not offer a high return-on-investment.

Isolation means no difficult relationships… and no support.

The Trump Administration’s foreign policy presumes we’ll never desperately need anything from our recently estranged allies. It might be popular with Trump’s base, but it puts all Americans in real danger during unanticipated need.

While we cozy up to dictators around the world we’re pushing away Canada, Mexico, and the European Union, places previously inclined to help us out in a pinch. Less than a decade after he commanded an Allied invasion of Europe, Dwight Eisenhower had this to say about isolationism:

“No nation’s security and well-being can be lastingly achieved in isolation but only in effective cooperation with fellow-nations.” President Eisenhower, 1953.

Ike made his career on going to war with nations that would later become some of our closest allies, something about his endorsement of international cooperation (after seeing the alternative close-up) carries extra significance.

Even though we have considerable natural resources, the best-funded military in human history, and tremendous pull in the global economy, we are not immune to catastrophe. In a time of need who do you want on speed-dial… NATO or North Korea?

The nightmare scenario.

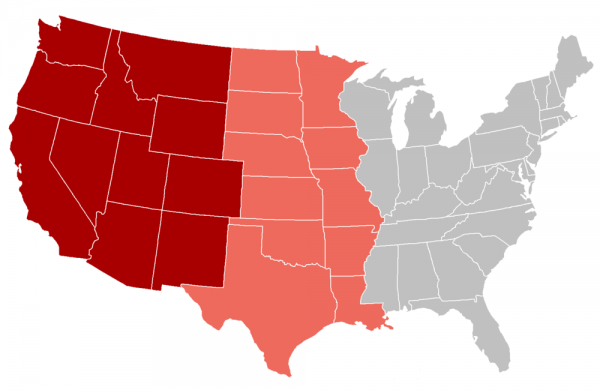

Other parts of the world are also experiencing rising nationalism and looming water problems, but we have something they don’t: the American West.

The American West, it turns out, was settled during an historic wet spell. It’s incredibly arid and getting dryer. In fact, one of the chief sources of water west of the Mississippi are mountain snow packs, and they’re shrinking. Because the West has limited water supplies, nature gives it no right to host large human populations. Yet there they are, precariously defying survival. That makes any disruption to water a disproportionately big problem to the over 75 million people that live in the West, because they have little (or nothing) to fall back on.

Imagine if a Flint-like crisis found its way to Phoenix, one of the ten largest U.S. cities. Say negligence led to a contaminated water supply. While authorities seek to fix that nightmare over several months, if San Francisco concurrently experienced an earthquake that took down its water utilities for any significant portion of time… the United States would suddenly be brought to its knees.

That’s right about when you’re going to want assistance from Canada.

The Canadians boast 7% of the world’s annually renewed water for their own use, while sporting only 0.5% of the global population. If you count lakes and glaciers, they’ve got a whopping 20% of the world’s total freshwater supply. In other words: they have a tremendous surplus. They’re also working on securing their water infrastructure risks.

As our northern neighbor, they’re the only country with the ability to quickly and economically transport emergency potable water assistance to us… because they can do it by land. Because of its weight, water really can’t be transported by air from (for example) the European Union in a massive, relatively cheap way… even if they wanted to. Which they probably won’t.

When you imagine a world in which even one or two of eleven Western States succumb to shortsightedness on water policy and desperately need assistance, it kind of makes steel tariffs on Canada look woefully arrogant.

Connect with us