It’s not your father’s sports section anymore.

Ryan MurthaBlockedUnblockFollowFollowingDec 3

“The Crime of the Big Leagues!”

This was the headline splashed across the front page of the Daily Worker, the United States’ most widely read communist circular of the mid-twentieth century. The journalist behind the giant font was Lester Rodney, the paper’s longtime sportswriter and editor. Rodney, himself a member of the Communist Party until 1956, did not just regurgitate for his readers the events of yesterday’s ballgame. No, he used his column to draw attention to the injustices endemic to sport, and explained how they mirrored those same injustices in society at large. In the case of the above headline, Rodney was taking aim at Major League Baseball’s embargo of black athletes. For years he wrote about the color line in professional baseball, hammering the men who enforced it. But though he saw this as the biggest story in the game at the time, his voice was a lonely one.

After Rodney left the Daily Worker in 1956, political sports writing all but vanished for the remainder of the 20th century. Sport has historically been viewed as a form of escapism. As sportswriter Howard Cosell put it, the “number one rule of the jockocracy” was that pro athletes and politics should never mix. This was echoed by reporters on the other side of the sport-politics divide as well, such as the Washington Post’s E.J. Dionne, who, in an article criticizing ESPN for hiring Rush Limbaugh as a commentator, wrote that

Most of us who love sports want to forget about politics when we watch games. Sports, like so many other voluntary activities, creates connections across political lines. All Americans who are rooting for the Red Sox in the playoffs are my friends this month, regardless of their ideology.

Conservative social critic Jonah Goldberg agreed, penning the column “Sports and politics mix like oil and water,” in which he celebrated sport’s ability to help people reach across the aisle. But if you treat sport as its own little world, floating lazily apart from the banal problems of the day, you will invariably end up taking the conservative view of it. You endorse the status quo, bowing to the authority of management over labor. As Frank Deford, famous sportswriter and founder of the nation’s first daily sports paper, said, “I kill myself when I think that when I ran The National neither I nor the bright people on that paper thought we really ought to examine the NCAA. We never said that. We just accepted that. We took it at face value. We should be ashamed of it.” In truth, apoliticism in sport is impossible, a fact that few sportswriters addressed, if they were aware of it at all.

If you were to look at any number of sports blogs today, you wouldn’t be wrong to be incredulous at this description of sports writing’s past. A quick survey of some of the most popular sport news sites on a random November day shows frontpage stories on unjust player compensation structures in MLB, hypocrisy and commercialization in the NFL, sexual harassment claims in professional basketball, and some more, different unjust labor compensation practices in MLB. The wall that had previously insulated sport from the chaos of the everyday has been sundered. Now, issues of race, climate, gender, sexuality, and class feature prominently in any worthwhile publication. And for this, we can thank a man who was never even trained as a journalist: Dave Zirin.

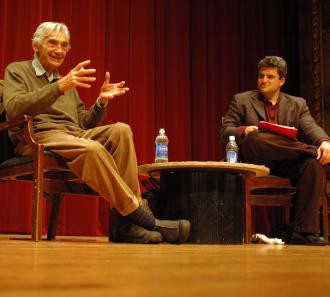

Zirin, a proud socialist, is today the sports editor at The Nation, one of the country’s most influential and widely-read progressive publications. He regularly appears on MSNBC, ESPN, Democracy Now!, and other media platforms. He has published ten manuscripts. Most notably, he was tapped by leftist historian Howard Zinn to add to the latter’s series of books, A People’s History. This gave us A People’s History of Sports in the United States. Zirin has written biographies of some of America’s most prominent activist-athletes: boxer Muhammad Ali, footballer Jim Brown, and sprinter John Carlos. His exposé on the 2016 Olympic Games, Brazil’s Dance with the Devil, is largely responsible for the scrutiny the country faced for the human rights violations that took place during the leadup to the event. If you spend any time at the intersection of sport and progressive politics, it’s impossible to avoid his work.

Today, Zirin told me about reporting on sport and politics, “It’s gotten crowded,” something that’s surprised even him. In an address at last year’s Nation Institute gala, Zirin proclaimed, “We live in a world where the sports field is a site of tenacious resistance. And that’s a sentence, Lord knows, I never thought I would say.” There is certainly an extent to which athletes have gotten more vocally political over the past decade, but it is also true that politically active athletes now just have more sympathetic reporters willing to cover them. Regardless of the causes, today Zirin is something of a patriarch to a generation of progressive sportswriters following in his footsteps, though he is still learning to navigate the new phenomenon of having to share his beat. As he told Bryan Curtis of The Ringer, “When I started doing this, in 2003, it felt a little lonely, like I was in a phone booth yelling this stuff. I didn’t know, or have access to, a community of sportswriters who felt similarly.” That that is no longer a problem is largely thanks to Zirin’s decade-plus of reporting on the intersection of sport and politics. Now, he told me,

There is this layer of writers who do this kind of work and I remember a lot of them when they were in college getting in touch with me, asking me questions about how to get into it, how to do it, what kind of resistance I came up against in doing it. And I try to talk to them as much as possible, if for no other reason than that I didn’t really have a lot of people to talk to.

Though he wouldn’t name any names, it’s not hard to look around the sports writing landscape and see Zirin’s point of view coopted by many younger writers. Most prominently, there’s Patrick Hruby at The Atlantic and Jessica Luther at Huffington Post, both of who regularly hammer the NCAA for its various abuses of its power; Jamelle Hill, who has become an authority on race and sport; and virtually the entire staffs of prominent sports blogs like Deadspin and Vice, both of which regularly parrot Zirin’s positions on a range of topics from stadium financing to doping to compensation for college athletes.

But it took years of solitary work to cultivate such a vibrant ecosystem of progressive sportswriters and readers willing to support them. Zirin’s early struggle was twofold: first, to convince sports fans that political issues are inseparable from sport; and second, to convince his fellow progressives that sport is a front worth fighting on. As passionately as many fans may disagree with his first point, the second was contested just as sharply by his fellow leftists. As none other than Noam Chomsky, one of the intellectual titans of the American Left, wrote,

Sports keeps people from worrying about things that matter to their lives that they might have some idea of doing something about. And in fact it’s striking to see the intelligence that’s used by ordinary people in sports [as opposed to political and social issues]. I mean, you listen to radio stations where people call in–they have the most exotic information and understanding about all kinds of arcane issues. And the press undoubtedly does a lot with this […] Sports is a major factor in controlling people. Workers have minds; they have to be involved in something and it’s important to make sure they’re involved in things that have absolutely no significance. So professional sports is perfect. It instills total passivity.

Zirin demurred. His thesis is this: sport is not just a distraction, another opiate of the masses. It can be in fact a tool for liberation. As he wrote in his very first column at The Nation, “It can become an arena where the ideas of our society are not only presented but also challenged. Just as sports can reflect the dominant ideas of our society, they can also reflect struggle.”[16] In history according to Dave, you cannot talk about women’s rights without talking about Billy Jean King; you can’t write on queer history without having a chapter on Martina Navratilova or Renee Richards; and chronicling the struggle for black liberation necessitates including the stories of Muhammad Ali, John Carlos, and Tommie Smith. Zirin extrapolates on his thesis in the introduction to A People’s History of Sports in the United States, writing

In an era where the building of publicly funded stadiums has become a substitute for anything resembling urban policy; in a time when local governments build these monuments to corporate greed on the taxpayers’ dime, siphoning millions of dollars into commercial enterprise while schools, hospitals, and bridges decay, one can hardly say that sports exists in a world separate from politics. When the sports page can no longer be contained in the sports page, then clearly we need some kind of framework to take on and separate what we love and hate about sports so we can challenge it to change.

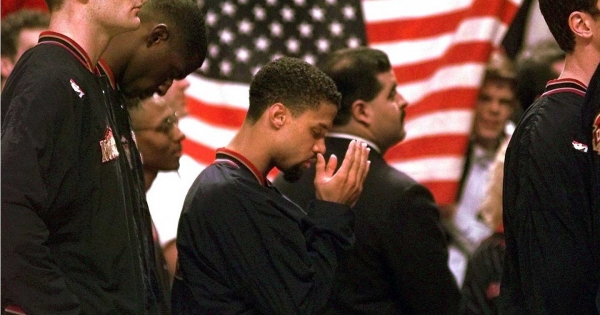

Zirin grew up a sports fan in New York City before moving to St. Paul to attend Macalester College, intent on becoming a teacher. Like many people, he traces his radical roots back to these college years, where he says he engaged in “resistance organizing on a host of issues.” But it was a somewhat circuitous route before he found his true vocation. Zirin told me that he had his eureka moment in the 1996 when professional basketball player Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf refused to stand for the National Anthem, was suspended and then subsequently drummed out of the league. He explained: “Then, someone on ESPN is talking about [Abdul-Rauf] following in the tradition of the activist athlete. I’m like, ‘What the hell is an activist athlete?’” As he said in a separate interview,

That really opened my mind up because I had no idea, even being such a big sports fan, that there was a tradition of these sports radicals; that there were these political athletes and that any tradition between politics and sports even existed. At that point, the seed was planted in me head […] for [The People’s History of Sports in the United States]. And I really wanted to fine a book that chartered that tradition, but it didn’t exist.

From there, the education of Dave Zirin began. Originally a teacher in the Washington, D.C. area, he made the jump into writing professionally, starting off at the small paper where he sold ads and wrote for $250 a week. He then moved on to the black-owned Prince George’s Post where the editors encouraged him to explore the intersection of sport and race, giving him his own column “The Edge of Sports.” Zirin’s columns caught the attention of Dave Meggyesy, the NFL linebacker-turned-anti-war activist, who sent the columns to a New York Times writer who in turn introduced Zirin to the editors at The Nation.

Zirin mentioned a few books as being formative for him as he pieced together what he wanted to do. One of these books is the Marxist writer Mike Marquesse’s Redemption Song: Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the 1960s. Zirin told me this book was so impactful for him “because I felt like that was not only a great hidden history but it also spoke about politics in a way that I felt was a model for the kind of sports writing that I wanted to do.” Zirin would actually end up writing a new forward for this book when it was republished in 2005.

In a separate interview, he mentions Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s autobiography Giant Steps as being equally eye-opening. Giant Steps, he said, helped him “make the journey from just being a freaky sports fan to actually looking at athletes as people and the politics of athletes.” Additionally, reading Joan Ryan’s infamous Little Girls in Pretty Boxes, he said, “just left a tremendous impression on me,” calling it “an excellent example of sports as investigative journalism.”[24] Putting Ryan’s book up next to Zirin’s Brazil’s Dance With the Devil, it’s easy to see the influence of her style on him.

Though Zirin’s niche interest made it so that there was no professional blueprint to follow or colleague to lean on, he does credit one man for helping guide him on his way: sportswriter Robert Lipsyte. Lipsyte, the man who brought Zirin to The Nation, was a longtime writer at the New York Times, and one of the most respected voices in American sports. Zirin has referred to him as his “personal Yoda”, though Lipsyte’s writing may not have been as explicitly progressive as Zirin’s is. But for his time, Lipsyte’s work was revolutionary, as he granted his subjects the agency that few sportswriters did. As Zirin told me, “It was more that Lipsyte heroically championed athletes in real-time when a lot of sportswriters didn’t — like Ali, like Billy Jean King. And so he was just politically sympathetic is the way to put it.”

Being the only one consistently writing about sport and politics, Zirin has worn many hats over the years. Some weeks he was an investigative reporter, sometimes a editorialist, and sometimes a media critic. The last of these three is probably the most useful in terms of judging his impact on the larger cultural landscape. It is only by seeing how large the gap ways between Zirin and more mainstream writers in aughts that we can grasp how radical the shift in the industry over the last decade has been, when now the revolutionary has become almost banal. Zirin saw that, despite their larger than average bank accounts, athletes were workers, and as workers were often exploited by their bosses. So like Lipsyte before him, he took up their cause, defending athletes at every turn, but especially when most of the media would be piling on.

When Michael Vick was indicted for his role in a dog fighting operation, he became the most hated man in America. Michael Ventre at MSNBC called for him to be “suspended for life,” while Michael Wilbon at the Washington Post was even more drastic, writing that he would “like to see Vick locked in a cage with six to eight of those pit bulls and nothing but his hands to use in his own defense.” Zirin, however, pointed out the hypocrisy of how American society celebrates the equally violent sport of football, writing “Let’s turn the magnifying glass on a society that condones so much violence in war, film and sport. […] Let’s ask why some of these fans can decry the treatment of dogs but barely acknowledge the pain of Earl Campbell.” He was the only writer at a national publication to make note of the racial and class issues at play in the response to Vick’s indictment. In future articles, he would often use the pearl clutching about the scandal to criticize the lack of concern over what he saw as more important issues: “Forget about death and dismemberment abroad, we have some dead dogs in Michael Vick’s Bad Newz kennel!” Once Vick finished his sentence, Zirin was again the lone voice saying he should be allowed back in the NFL, pointing out how athletes who committed much worse crimes were allowed to continue playing, mostly because they weren’t as high profile as Vick was. But also Zirin uses the Vick story as a way to talk about the “national disgrace” that is the American prison system. He argued that “the very political forces — and they are bipartisan — that have made the United States the prison capital of the world are at work in the saga of Michael Vick,” and by allowing him to return to his job, the NFL could strike a blow for ex-convicts everywhere by “sending a necessary message that prison does not make you a pariah.” Again, remember this is a sports column.

Barry Bonds was another unpopular figure who Zirin spilled a lot of ink defending. Zirin took issue with the fact that that owners had no problem with steroids as long as they were making money, and only objected to their use when it became convenient from a business perspective. Zirin believed MLB targeted Bonds for what had been a systems-level issue. As he wrote, “Dropping an entire juiced era on one person’s shoulders is like arresting an ace computer tech for Enron’s extensive fraud while leaving Lay, Skilling and company alone.” Obviously, this was not a popular opinion among his fellow sportswriters. Tom Sorenson of the Charlotte Observer referred to Bonds as “OJ Lite,” which may have been one of the politer monikers Bonds picked up at the time. Zirin criticizes writers like Sorenson for “spraying lighter fluid on the fire” of racism, which was an integral — but ignored — aspect of the discourse surrounding Bonds. Zirin was virtually alone in writing about the power dynamics at play in the investigation of baseball’s steroid era, calling the Mitchell Report a “magical fishing net that captures minnows but lets the whales swim free” for ignoring the role of billionaire owners in the propagation of anabolics and human growth hormone. This is a running theme through Zirin’s writings: everything goes back to power. Whether that power is rooted in race, class, or gender differences, that is the underreported story that, according to him, we should all be paying more attention to.

Lebron James and Alex Rodriguez, two notoriously unpopular athletes at various times in their careers, also found themselves under Zirin’s protection when the mob came. When A-Rod was being lambasted in the papers for steroid use, Zirin again was quick to point out that to true fault for this scandal, as always, lied with those in power, the owners “who have yet to face any kind of Congressional subcommittee, grand jury or operatic media melodrama for their role in cheapening the sport.” And when James moved to Miami from Cleveland, Zirin was one of the only writers to defend the move. Instead, he criticized Cleveland Cavaliers owner Dan Gilbert for his lack of gratitude. Zirin instructed Gilbert to “spare us the moral outrage,” calling his reaction “utterly graceless, classless” given “how much coin James had put in Gilbert’s pocket.” In typical Zirin fashion, he then proceeded to lambast Gilbert for the billionaire’s role in exacerbating the foreclosure crisis through his role as the CEO of Quicken Loans, arguing that “If anyone has stabbed the people of Ohio in the back, it’s not Lebron James: it’s Dan Gilbert.”

Zirin freely criticizes his fellow media members not just to defend athletes, but when he thinks their tongues get to close to the boots of power as well. As Zirin wrote in 2008, “There is money and fame for those willing to “play ball.”” Where others will cozy up to management and owners in order to get access, Zirin often takes to the streets for his stories, depending on quotes from The People: fans, bloggers, activists, and community members. He criticized the way that mainstream publications covered sports, and took issue with ESPN’s programming, which he says now just involves sportswriters talking to each other. As he put it, “They’re the only people they can identify with.” He criticized the privilege and isolation that marked most writers, and was likely the only one in his industry to celebrate the rise of blogs for giving access to writing platforms to larger groups of people. When asked what the highlight of his career as a sports journalist was, he gave an equally nontraditional, populist response: “To me, going into the Oakland Juvenile Detention Center and speaking to […] young people about their thoughts about sports was one of the most moving experiences in my life.”

Zirin has little time for collegiality when it comes to those writers who cross him. He took the aforementioned Jonah Goldberg to task for misrepresenting John Carlos and Tommie Smith in a Los Angeles Times column, writing that “You could tell right away that Goldberg didn’t read a book, an article, even a fortune cookie, about the 1968 Olympics before whipping out the laptop,” before going through Goldberg’s column line by line to explain its numerous fallacies.[43] ‘Combative’ is his default mode, especially when it comes to the Olympics. Every two years, Zirin will reliably churn out numerous articles criticizing NBC’s coverage, its Americentric view of the event, as well as the jingoistic, Cold War-era rhetoric it uses. As he wrote in 2008 (and has been repeating ever since),

One of the bizarre contradictions of the Games is that they are meant in theory to promote internationalism, yet television coverage has historically been focused almost exclusively on US athletes. During this year’s Games this tendency has been even more egregious, with long tape delays and Cold War rumblings combining to produce a spectacle that feels more like sports as propaganda than sports as bridge builder.

Aside from its injection of nationalism into coverage of the Olympics, NBC consistently ignores what Zirin sees is the real story here (note the trend): the politics behind the Games. He lamented, “NBC has thus far treated the Games with the political depth of an old Hope-Crosby road picture. They might as well call their coverage, Costas Goes to China.” Zirin took issue with Washington Post writer Thomas Boswell’s characterization of reporting at the Games, wherein he wrote that “We had little alternative but to be a conduit for happy-Olympics, progressive-China propaganda.” While Zirin applauded Boswell for his honesty, he believed that

Boswell and the press made a choice the moment they stepped on China’s soil. They chose not to seek out the near two million people evicted from their homes to make way for Olympic facilities. They chose not to report on the Chinese citizens who tried to register to enter the cordoned off “protest zones” only to find themselves in police custody. They chose not to report on the Tibetan citizens removed from their service jobs by state law for the duration of the Games […] They chose not to ask and re-ask the question of why the Games were in Beijing in the first place.

Unlike most writers who make their bones criticizing the men and women on the field, it’s hard for an athlete to really earn Zirin’s ire. His scorn is reserved almost exclusively for the owners and other power brokers he says are ruining the game. It’s only ever those athletes who either break with the player’s unions, or who Zirin sees as not doing enough to further progressive causes, that he will use his column to rail against. His biggest target in this regard has been Tiger Woods. Unlike most writers, Zirin had no interest in Woods’s extramarital affairs — in fact, he criticized what he saw as this country’s “prurient obsession with black male sexuality.” Instead, he took issue with such a prominent colored athlete refusing to use his influence for good. Zirin bemoaned that he has “established a reputation for reticence off the greens. Woods has refused to take stands on issues that should hit close to home,” and Zirin sees that as the ultimate failure. He even sees the non-profit that bares the golfer’s name, the Tiger Woods Foundation, as being as much a sham as the man himself is for its partnership with Chevron. As Zirin explains,

Chevron is in full partnership with the Burmese military regime in the Yadana gas pipeline project, the single greatest source of revenue for the military. […] These are the same people who are blocking international aid workers from assisting the victims of Cyclone Nargin. The death toll has been estimated at 78,000, but the number can explode as disease spreads and help isn’t allowed through the military lines.

If you think that Zirin couldn’t hold Tiger at least partially responsible for these 78,000 deaths, you’d be wrong. Zirin insisted that this, “Tiger’s partnerships with toxic waste dumper Chevron and financial criminals in Dubai deserve far more scrutiny” than his cheating and promiscuity did. Woods’s father promised his son would be a humanitarian, a bringer of peace. The hypocrisy of Tiger’s actions in light of this oath was just too much for Zirin to stomach.

That Michael Jordan was also excoriated by Zirin illuminate exactly what it is the latter hates: those athletes who find fame and success but would rather protect their new social capital than wield it to call for change. As Zirin wrote, “Given the heights [Jordan] commanded, it’s difficult to think of anyone in the history of American cultural life who did less with more.” Despite his socialist tendencies, Zirin doesn’t begrudge these athletes their wealth. It is their refusal to use that wealth that he hates.

Zirin by no means limits himself to criticizing those connected to sport. His favorite and most regular punching bags have been Dick Cheney and George Bush, though he gives himself license to write about the latter by pointing out that he used to own the Texas Rangers. These two men offered Zirin a ready metaphor that he proved incapable of passing up. In an article on the aforementioned Tiger Woods, Zirin wrote that the golfer “sees the political world the way Dick Cheney sees the Bill of Rights: frightening and to be avoided at all costs.” And on the Superbowl Halftime show, he described a sponsor Firestone as seeing “unions the way Dick Cheney sees the International Criminal Court.” He criticized Bush’s appearance at the 2008 Olympics: “Remember Nero fiddling while the world burns? Nero’s got nothing on George W. Bush. Hell, at least Nero was displaying a demonstrative skill.” Joe Lieberman was another frequent target, who he once compared to USA Basketball at its mid-aughts nadir: “Defeated, desperate, using every means to claw back towards relevance.” Obviously the Trump era and the new cast of characters it has brought to the national stage has been a boon for his heavy-handed prose as well.

Sport was always a jumping off point for what Zirin really wanted to talk about; economic inequality, housing scarcity, prison reform. You’ll never find Dave Zirin simply reporting the facts. He’s always making an argument, the same argument he’s been making for the past fourteen years: sports matter, and you should be paying closer attention, because they impact much larger issues. But as much as we can learn about Zirin from the positions he stakes out in his columns, it might be simpler to just look at whose names and words appear there. It’s rare to go more than a few weeks without coming across some quote from Zinn, or leftist political leader Eugene Debs, or the writer Eduardo Galeano. He samples liberally from the works of the socialist author Jack London and the activist poet Sonia Sanchez. Equally telling is the list of people he chooses to interview for the magazine, a non-comprehensive list which includes union leader Billy Hunter, Jim Brown, the mother of football player-turned-soldier-turned-corpse Pat Tillman, and progressive politician Ralph Nader. Obituaries from Zirin are reserved for only the true believers: the aforementioned Rodney and Zinn of course, along with South African activist Fatima Meer and poet Dennis Brutus. Zirin sees himself in the spirit of these people that he so admires: not just a chronicler of the events of the day, but himself an activist, in the trenches, working for change.

Zirin has no difficulty making the jump from sport to whatever larger issue he wants to address. A quote from Wizards center Etan Thomas about the soldier brought in to address the team turns into a critique of the war in Iraq; a column about the indictment of Barry Bonds turns into his own indictment of the Department of Justice instead; and the Michael Vick saga allows Zirin to take aim at the prison industrial complex. He’s not wrong to make these connections between seemingly innocuous sporting events and the systems that create them, though he eschews any attempt at subtlety while making them.

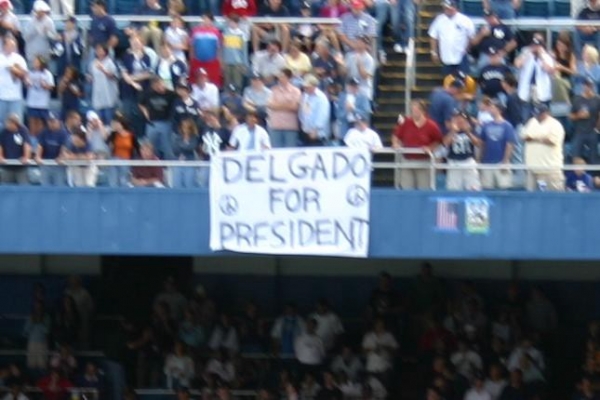

Zirin could, at times, be found guilty of idealism. In 2005, he suggested that New York Mets first baseman Carlos Delgado’s refusal to stand for the national anthem could be an integral part in ending American militarism in the Middle East. He wrote, “The latest polls show Bush and his war meeting with subterranean levels of support. Delgado could be an important voice in the effort to end it once and for all.” Two years later, he reported on a strike of the workers employed to clean the Baltimore Orioles’ stadium, suggesting that it “could open a new chapter in grassroots labor organizing not seen since the early days of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaigns.” In 2010, collective bargaining was underway between the NFL and its players union, when a group of athletes raised their fists together before a game. Zirin called this “perhaps the most widely-seen, collectively experienced display of labor solidarity in the history of the United States.” And when the Phoenix Suns as an organization came out against SB 1070, Zirin wrote that it was an act “without precedent,” creating an opening of every athlete “to stand up and he heard.” But his optimism is his animating force, and its unlikely he could have done his job so successfully if not for his fervent belief that someday the ghosts of the 1960s would stir and the spirit of resistance would return to the playing field.

Zirin has consistently been leading the way on all sorts of hot-button issues in sport. One prominent example would be compensation for college athletes. The topic only began to gain some mainstream traction in 2011 when The Atlantic published a cover story by the Pulitzer Prize-winning civil rights reporter Taylor Branch, “The Shame of College Sports.” Branch’s reporting received major media attention, and Frank Deford, one of the legends of the business, told NPR that it “may well be the most important article ever written about college sports.” But Dave Zirin had already been banging that same drum for years. Here’s Zirin in a 2008 interview, basically summarizing Branch’s article three years before it was written:

And college athletes being paid: to me this is just the biggest no-brainer in the world. I think every college athlete should get a stipend–it should be like their work-study. Now on top of that, in the real revenue-producing sports, they should get a piece of the pie. There’s something bizarre about the fact that if you’re a star college athlete at a big-time school, they will put your image on collector’s-edition Visa cards, so that you could then go buy things with that Visa card and get discounts on school merchandise, but then you don’t get a piece of that! Or that you can wear Nike shoes and run up and down the court, and the coach gets 300 grand in his pocket a year. And if you get injured, your scholarship is gone faster than you can say, “Oops!”

Today, most of the positions he staked out 15 years ago are orthodox throughout the industry. It’s only the most conservative writers that defend the NCAA cartel anymore, and it’s impossible for a team owner to get public funding for a new stadium without a host of articles analyzing the costs and benefits of the deal. Similarly, the number of cities able to bid for the chance to host the Olympics has dwindled dramatically. Zirin’s importance on the evolution of sports writing over the past decade is inarguable, but it may be worth asking what’s left for him now that his driving mission has been accomplished. By convincing the rest of the industry that the racial/social/financial aspects of sport are the story, he may have made himself less integral. But that’s a tradeoff he says he would gladly make.

Now, so many years removed from his first career, Dave Zirin now finds himself back in the classroom. This semester, he’s teaching his first ever college course: a history of sports class at Montgomery Community College. As he told me, he was enjoying “The opportunity to get away from writing for a little bit and be in a collective environment.” When I asked what’s next, he said

I’m going to do a young adult version of the book I did with Michael Bennett, Things That Make White People Uncomfortable. But other than that, the Jim Brown book was my tenth book in 13 years so I’m going to take a little break to get some perspective.

Taking a break for Dave Zirin still means churning out weekly columns at The Nation, and if you attend any sort of political action in the Washington, D.C. area, you’ll likely find him there. But for the man who has given perspective to an entire industry, a break seems well deserved. As early favorite subject, ballplayer, and Iraq War critic Carlos Delgado said, “sometimes, you’ve got to break the mold. You’ve got to push it a little bit or else you can’t get anything done.” Zirin pushed a lot of bit, not just breaking the old mold for sportswriters, but casting himself as a new one for others to follow.

Connect with us